It’s September, and (for me at least) that means the start of a new school year. And with that new school year comes a familiar sight in the gym: frat boys walking in and immediately setting up camp in small groups at the benches. After spending some time both reflecting on the barbell bench press as an exercise and wondering whether or not these frat boys realize the human body contains more than one muscle group, I’ve decided to write a post sharing my views on the bench press and where it belongs in a training program–if it belongs at all.

Why I Rarely Use the Barbell Bench Press

For all of you geniuses thinking the answer is because I’m small and ashamed I can’t put up big weight, I can neither confirm nor deny that statement. Regardless, that’s not the crux of my case for rarely putting the barbell bench press–a staple of strength and conditioning programs seemingly since the dawn of man–in programs I write.

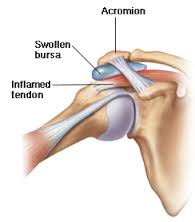

Let me preface my case with this: I’m not saying that the barbell bench press is a “bad” exercise. It’s been a staple of programs for a reason–it’s a basic, effective pressing movement. But there are a few drawbacks. First, shoulder problems are a common occurrence among many who bench regularly. Since the scapulae are pinned “down and back” during the barbell bench and thus cannot move, when the humerus is pulled beyond even with the trunk during the eccentric portion of the exercise the acromial space between the acromion process of the scapula and the humeral head narrows, potentially pinching and irritating the tendons of the rotator cuff muscles (a condition known as impingement syndrome). Granted, there are ways to reduce this risk, such as keeping your elbows tighter to the trunk as opposed to flared out wide, but since my first responsibility as a strength coach is to “do no harm”, I always tend to err towards the safe side, especially when there are plenty of other good options available.

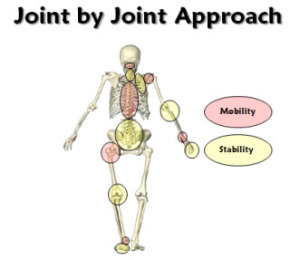

Closely related to this point is that since the scapulae are pinned down and back, you’re training a movement pattern that doesn’t really transfer well to everyday movement. In almost any pressing

movement we as humans do either on the field of play or in activities of daily living, the scapulae are free to move along the ribcage. Considering Mike Boyle’s Joint-by-Joint Approach, you might think that since the scapulae require stability more than mobility then the bench press would be a great fit. However, the stability required in a bench press is static stability–the scapulae are not moving. In normal human movement outside of the gym, where the scapulae are usually free to move, they require an entirely different kind of stability–dynamic stability. In other words, it is more important that the scapulae are stable while they are moving than while they are locked in place. Mike Robertson covers this in great detail in this post.

The takeaway? I prefer dumbbell bench and push-up variations. The dumbbell bench allows for a more ergonomic movement, particularly in that you can take the humerus out of internal rotation (it’s locked into internal rotation in a barbell bench). This will open up a bit of space under the acromion process and can decrease the chances of irritation or impingement in the region. I especially like unilateral variations, as they elicit greater core activation due to the addition of instability in the transverse plane, and they also allow for a bit more scapular movement. In my eyes, though, the push-up is the king of all horizontal pressing exercises (so excluding overhead/vertical presses; that’s a whole different can of worms that I won’t delve into in this post). It allows the scapula to move perfectly freely over the ribcage, and it also requires considerable core stability–provided you’re doing them with correct form. Many think of the push-up as being too “wussy-ish” or whatever, but load it up with a heavy weight vest or chains and you’ll find it’s not so wimpy after all. Moreover, there are studies that show that the bench press and pushup elicit similar levels of muscle activity and comparable gains in strength when performed at the same load. While there are a few practical issues to consider–it’s logistically easier to load a heavy bench press, you can’t “spot” a pushup so failing a rep could be more dangerous, etc–it is clear that the pushup is an effective pressing exercise that should not be discounted simply because you’re not stacking plates on a bar. Below are a few videos that Rob and I filmed explaining how to perform some alternatives to the barbell bench press.

Dumbbell Bench Press

1-Arm Dumbbell Bench Press

Pushup

Band-Resisted Pushup

Pushups with Chains

I want to reiterate that I’m not bashing the barbell bench. Powerlifters, bodybuilders, and weekend warriors who can do it with good technique and without pain can and should implement it to some degree in their programs. In this article, Bret Contreras and Sam Leahey talk about how people generally can’t dumbbell bench more than they can barbell bench, and that studies show that triceps EMG activity is greater in a bilateral bench than a unilateral bench. In this way, it seems that the bilateral bench may be superior than unilateral variations for muscular hypertrophy and strength gains.

It is important to understand, however, that size and absolute strength are almost never the only goals in a training program, regardless of whether you’re an athlete or not; they are just two of a myriad of things that need to be addressed. Grooving proper movement patterns is key, for example, as is injury prevention. Due to considerations such as these, I think that for the majority of people–particularly athletes and those with a history of shoulder issues–there are better options.

For better or worse, though, the barbell bench has been such a staple for so long that many can’t control their ego and insist on being heroes–they want to put up the big weight. If you fall under this category, compromise and substitute the barbell bench for a floor press. You get a similar movement and solid chest activation without the potential shoulder issues caused by excessive humeral extension, as that end range of motion is restricted by the floor. Using a bar with a neutral grip–like the multipurpose bar Eric Cressey recommends in this article on baseball pitchers and benching–is also a great idea for avoiding the humerus getting locked into internal rotation.

If you haven’t given the floor press a try before, I recommend you experiment with it. I’ll leave you with two videos Rob and I filmed explaining how to perform the exercise and some of its variations.

Barbell Floor Press

Dumbbell Floor Press